Sally Field’s powerful performance in Norma Rae (1979) cemented her place as one of Hollywood’s finest actresses.

Her portrayal of a determined textile worker fighting for labor rights earned her an Academy Award and left audiences in awe.

But behind the scenes, the path to that unforgettable performance was marked by emotional struggles, self-doubt, and even a few broken ribs.

Holidays, the 40-hour work week, healthcare, worker safety laws, child labor protections, minimum wage — the list goes on. None of these crucial worker rights would exist without unions, even for those not in them.

In Norma Rae, Sally Field’s iconic portrayal of a woman standing up for her rights and the rights of her fellow workers is still a reminder of how far we’ve come.

Sally’s performance not only earned her the recognition she deserved, but also likely inspired future powerhouse performances from actresses like Julia Roberts in Erin Brockovich and Meryl Streep in Silkwood.

But as mentioned, she had to pay a high price for her iconic role.

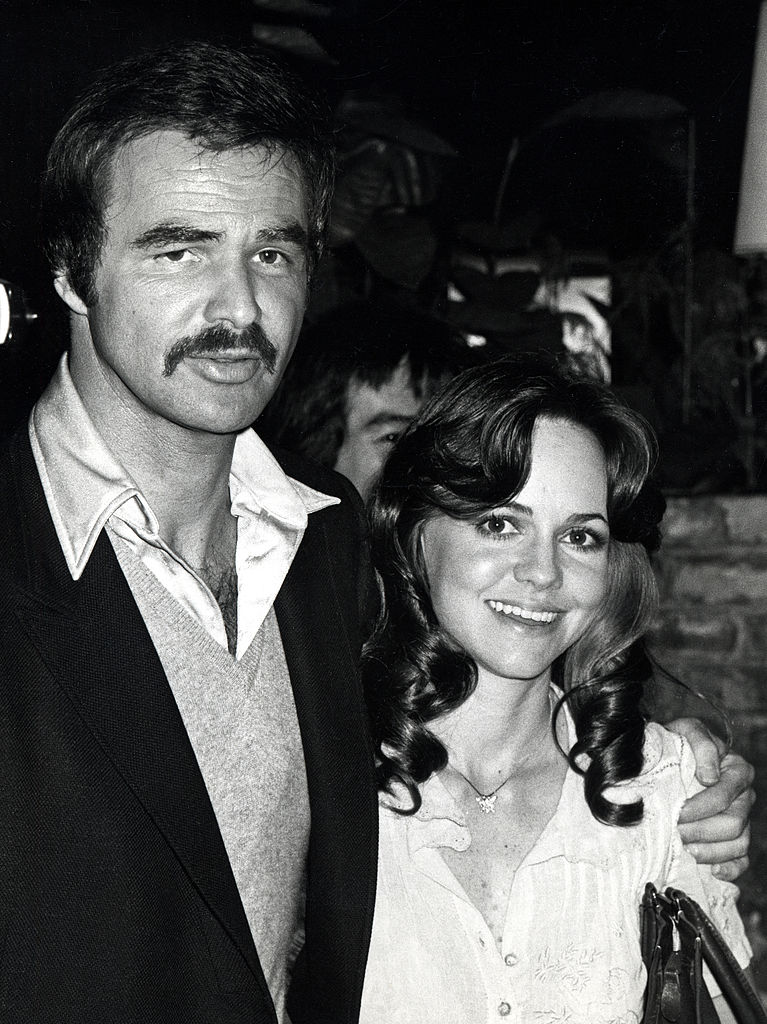

Did the film against Burt Reynolds’ advice

Before Norma Rae, Sally Field was still trying to break free from her early TV image as The Flying Nun and Gidget. Hollywood didn’t take her seriously, and she knew she had to prove herself. When the opportunity to play Norma Rae Webster came along, she saw it as a chance to redefine her career — but it wouldn’t be easy.

A major problem was that Sally’s then-boyfriend, superstar Burt Reynolds, was being unsupportive and jealous.

Reynolds didn’t approve of Field taking on the role of Norma Rae and famously told her, ”No lady of mine is gonna play a whore.” When Field tried to explain that it was just a part she was playing, Reynolds mocked her, saying, ”Oh, so now you’re an actor… you’re letting your ambition get the better of you.”

Sally recalled the moment she first watched the film, sitting in a small screening room at Fox Studios next to her mother, feeling an overwhelming fear.

”What flashed through my head was the fear that I wasn’t enough to hold an audience for two hours,” she reflected.

Proposed on the last day of filming

The high-profile relationship between Sally and Reynolds began after he asked her to star in Smokey and the Bandit. At first, their connection was instantaneous and intense, but it soon turned into a nightmare for Sally.

She describes how the movie star quickly began to ”housebreak” her, dictating ”what was allowed and what was not,” which led her to become a ”shadowy version of herself.” His negative attitude toward her role in Norma Rae was just the latest manifestation of all the criticism Burt had for Sally.

Despite his objections, Field went ahead with the role. On the final day of filming, Reynolds showed up on set and proposed with a diamond ring. Field recalls the moment, saying it felt ”not me,” and she didn’t accept his proposal. The awkward exchange left her with little to say other than a simple, ”thank you.”

After Norma Rae wrapped up, Field began to feel herself growing more confident and independent – it was almost as if the role and her personal life collided. Field noticed her personality starting to ”flare out,” which did not sit well with Reynolds.

He responded with ”shocked disapproval.”

Worked in the mill every day for two weeks

As many might recall, Norma Rae is inspired by the real-life story of Crystal Lee Sutton, a textile worker from Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, where the fight for a workers’ union unfolded at a J.P. Stevens Textiles mill.

Field auditioned for the role while briefly visiting New York from the set of Hooper and was chosen for the part, which had already been passed over by several actresses. (According to her autobiography, Shirley MacLaine had initially expressed interest in the role.)

To fully prepare for her role, Sally Field dove deep into the lives of Southern mill workers. She and Beau Bridges conducted thorough research by spending time working in a factory, according to IMDb. Field immersed herself in the environment, adopting the workers’ mannerisms, understanding their struggles, and experiencing the physical and emotional exhaustion they faced.

”I worked in the mill every day for two weeks; not all day long, I didn’t have an 8-hour shift, but I felt like it. I guarantee, two hours in that weaving room felt like 8 hours anyplace else, because the vibration is like the motion on a ship, the whole room shakes and it makes you seasick. So you have to get used to it, get your sea legs. All the actors and the crew were saying, ‘I don’t know how they do it’,” Sally Field explained.

Where did they shoot Norma Rae?

While the real story of Crystal Lee Sutton unfolded in Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina – but Norma Rae was actually filmed in Opelika, Alabama.

Filming kicked off in May 1978, and the town’s locals stepped in as factory workers for the scenes. The Opelika Manufacturing Corp. was transformed into the textile mill for the movie, while The Golden Cherry Motel, which has been around since the 1940s, was used for the motel scenes.

Although the Opelika textile mill, which had been the first in town since 1900, closed down in 2004, it wasn’t demolished until 2016. During filming, one tricky detail was the constant hum of the machines at the mill, which made it hard to catch the actors’ lines on camera.

A huge event

When Hollywood came to the small town of Opelika, Alabama, it was a huge event. During the filming, Field had a meeting with then-Gov. George Wallace, while many locals eagerly awaited the possibility of megastar Burt Reynolds visiting his girlfriend on set. The excitement in the air was palpable.

Burt did make a few visits to the filming locations, but it was Sally Field, the film’s leading star, who truly left a lasting impression on the local community.

“She was a lovely lady,” says Warner Williams, who was active with the Opelika Chamber of Commerce during the filming of Norma Rae. “Days before filming, she wore old ragged clothes and hung around the mill, psyching up for her character.”

The real Norma Rae – Crystal Lee Sutton

Crystal Lee Sutton was born on December 31, 1940.

She grew up in Roanoke Rapids, a town that, as she remembers, was sharply divided between workers and managers.

”All my life, textile workers were looked down on. The doctors and lawyers and managers didn’t want their children to associate with us. They always had new clothes, they were the smartest. They were the cheerleaders, and the majorettes — anything outstanding, it came from your higher class of people,” Crystal told Washington Post in 1980.

Crystal Lee started working when she was just 16. By 17, she was already working the 4 p.m. to midnight shift at a textile plant, filling batteries. At 19, she became a mother for the first time, and by 20, she faced the heartache of losing her husband.

At 21, she had her second child, and in 1965, her third arrived.

Known for her courageous stand as a union organizer, Crystal Lee Sutton made headlines in 1973 when she was fired from her job at the J.P. Stevens plant in Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, for her pro-union activism.

At that time, Sutton was a 33-year-old mother of three, working at a wage of $2.65 per hour, folding towels. Her battle for workers’ rights was immortalized in the 1979 film, which was inspired by the 1975 book Crystal Lee: A Woman of Inheritance by New York Times reporter Henry “Hank” Leifermann.

Director Martin Ritt once said of Crystal Lee Sutton, ”I’ve known a lot of women in my life, most of them much more educated and sophisticated, who would not have had the balls that she had.”

Crystal Lee Sutton’s honest take on the movie

Crystal Lee Sutton, the woman behind the story of Norma Rae, was not pleased with how the film turned out.

She believed it should have been a docu-drama. Sutton found the movie ”funny” and admitted, ”It made me cry in parts and it made me laugh… I just thought if they’re going to spend millions of dollars making a movie, I wanted it to be a good educational union movie, not a soap-opera love story like you can see every day on TV.”

Sally Field also cried after watching the movie. She admitted that the overwhelming reaction from the audience at the Norma Rae premiere at the Cannes Film Festival brought her to tears.

Sued the creators of the movie

Norma Rae grossed $12.5 million, yet Sutton received no profits from the movie.

The same was true for the book Crystal Lee — she received nothing from it either.

After the film’s success, Crystal Lee Sutton had to sue 20th Century-Fox to receive a small settlement, eventually getting $52,000 — half of which went to taxes. After paying off some of her loans, Crystal used the remaining money to buy her third husband a secondhand Pontiac Trans-Am. ”He helped me and supported me through all this, and he deserved something,” she told Washington Post.

Her husband, Preston Sutton, expressed his deep admiration for her courage:

”I told my wife I don’t give a damn if we have to live in a car, I’m proud of what she done and what she stood for,” Preston Sutton said. ”You better damn well believe there’s a lot of people that would like to have the guts to do what she did.”

Sally Field and Crystal Lee Sutton met once

One of the highlights of Crystal Lee Sutton’s life came in California in 1980 when she met Sally Field, who played her in Norma Rae. The meeting between the real-life inspiration and the actress, set up to promote the film, was a memorable moment.

Sutton recalled meeting Field at a reception, with cameras flashing as they posed together, their hands raised in a shared moment of triumph.

”We talked about children,” Sutton said. ”She told me if ever there was anything she could do for me let her know.”

Crystal Lee Sutton, the real-life woman behind the Oscar-winning film Norma Rae, passed away on September 11, 2009, at 68. She died of inoperable brain cancer at Hospice Home in Burlington, North Carolina.

Dolly Parton connection

In Norma Rae, Sally Field’s character sings along to Dolly Parton’s song ”It’s All Wrong, But It’s Alright” on the radio.

A decade later, Field and Parton would share the screen as co-stars in the beloved film Steel Magnolias, forming a memorable connection between the two icons.

The truth about the UNION sign scene

The iconic scene in Norma Rae, where she writes “UNION” on a piece of cardboard and stands on a table until her co-workers turn off their machines, is directly inspired by an event in Crystal Lee Sutton’s life.

This dramatic moment, which has become one of the most famous in U.S. film history, was a pivotal act of defiance by Sutton in 1978.

In the film, the character Norma Rae is called into the management office and fired after attempting to copy a racist letter.

Refusing to leave, she writes “UNION” on cardboard and stands on a table in the weaving room, holding it up for all to see. This act of bravery remains one of the most powerful and defining moments in cinematic history.

Crystal Lee Sutton herself recounted the real event: “I took a piece of cardboard and wrote the word UNION on it in big letters, got up on my work table, and slowly turned it around. The workers started cutting their machines off and giving me the victory sign. All of a sudden the plant was very quiet…”

The truth about the movie poster

One thing that has frustrated some people is one of the film’s movie poster.

Instead of featuring a determined Norma Rae in her work clothes holding the union sign, as you’d expect, the poster shows a smiling, more polished Sally Field simply raising her hands in the air. It seems odd, almost as if the union sign was intentionally removed.

There is an explanation for this shift in focus. Martin Ritt, the director, once stated that his main interest was in telling the personal story, admitting that he “couldn’t have cared less about labor unions.”

In a way, the movie Rocky also had an influence on how Norma Rae was marketed.

Tamara Asseyev and Alex Rose, the co-producers of Norma Rae, revealed in an interview that Rocky showed them the box office potential of a story about “a small person who succeeded.” This insight helped them sell the idea to 20th Century-Fox and Alan Ladd Jr., after it had been rejected by several other studios.

The escape from acute cuteness – broken ribs

Sally Field, long known for her sweet and light-hearted roles, had grown tired of being cast as the “cute” flying nun.

”I was so tired of being boring, but for a long time, I really didn’t have the guts to make any hard decisions,” she said.

So, Norma Rae was more than just a breakthrough — it was a turning point.

And Sally Field really threw herself into the role — so much so that during a scene where she’s struggling to avoid being shoved into a police car, she ended up breaking one of the actor’s ribs.

”You don’t expect to win anything, do you?”

But when Sally Field won the Academy Award for Best Actress, her emotions were a mix of disbelief and overwhelming joy. Hollywood had finally acknowledged her talent, but the road to this moment had been far from easy.

We now know that Field took on the film against Burt Reynolds’ advice, which ultimately led to the end of their relationship.

We also know that Reynolds refused to attend the ceremony with Field, despite her Best Actress nomination. And when Field told him she was attending the Cannes Film Festival, he was dismissive, asking in a frustrated tone, ”What the hell I intended to do there?” He dismissed it as a ”waste of time” and lashed out, questioning, ”You don’t expect to win anything, do you?” before hanging up the phone.

Thankfully, it was fellow actor David Steinberg and his wife, Judy, who came to her aid when Reynolds refused to be her date to the Academy Awards.

”David said, ‘Well, for God’s sakes, we’ll take you,’” Field recalled. ”He and Judy made it a big celebration. They picked me up in a limousine and had champagne in the car. They made it just wonderful fun.”

More than four decades later, Norma Rae remains one of the most powerful films about workers’ rights, and Sally Field’s performance continues to inspire.

But behind the triumph was a woman who gave everything she had to bring one of the most important characters in cinema to life. The truth? Success didn’t come easily — it was fought for, just like Norma Rae herself.